What Is The Parent Genes (Genetic Makeup) Called?

Genes come in different varieties, called alleles. Somatic cells comprise two alleles for every gene, with one allele provided by each parent of an organism. Often, it is incommunicable to determine which two alleles of a gene are present within an organism's chromosomes based solely on the outward advent of that organism. Still, an allele that is hidden, or non expressed by an organism, can still be passed on to that organism's offspring and expressed in a afterwards generation.

Tracing a hidden gene through a family tree

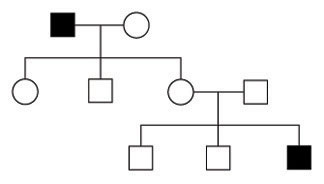

Figure 1: In this family pedigree, black squares bespeak the presence of a item trait in a male, and white squares stand for males without the trait. White circles are females. A trait in one generation tin can exist inherited, just non outwardly apparent before two more generations (compare black squares).

The family tree in Figure 1 shows how an allele can disappear or "hide" in i generation so reemerge in a afterward generation. In this family tree, the begetter in the first generation shows a particular trait (as indicated by the black square), only none of the children in the second generation bear witness that trait. Nonetheless, the trait reappears in the third generation (blackness square, lower right). How is this possible? This question is best answered by considering the basic principles of inheritance.

Mendel's principles of inheritance

Gregor Mendel was the beginning person to describe the fashion in which traits are passed on from ane generation to the adjacent (and sometimes skip generations). Through his breeding experiments with pea plants, Mendel established three principles of inheritance that described the manual of genetic traits earlier genes were even discovered. Mendel's insights profoundly expanded scientists' understanding of genetic inheritance, and they also led to the evolution of new experimental methods.

One of the central conclusions Mendel reached afterwards studying and convenance multiple generations of pea plants was the idea that "[you cannot] depict from the external resemblances [any] conclusions every bit to [the plants'] internal nature." Today, scientists use the word "phenotype" to refer to what Mendel termed an organism's "external resemblance," and the word "genotype" to refer to what Mendel termed an organism's "internal nature." Thus, to recapitulate Mendel's conclusion in modern terms, an organism's genotype cannot be inferred by just observing its phenotype. Indeed, Mendel's experiments revealed that phenotypes could be hidden in one generation, simply to reemerge in subsequent generations. Mendel thus wondered how organisms preserved the "elementen" (or hereditary material) associated with these traits in the intervening generation, when the traits were subconscious from view.

How do hidden genes laissez passer from one generation to the next?

Although an individual gene may code for a specific physical trait, that gene can be in different forms, or alleles. 1 allele for every gene in an organism is inherited from each of that organism's parents. In some cases, both parents provide the same allele of a given gene, and the offspring is referred to equally homozygous ("homo" meaning "same") for that allele. In other cases, each parent provides a different allele of a given cistron, and the offspring is referred to as heterozygous ("hetero" pregnant "different") for that allele. Alleles produce phenotypes (or physical versions of a trait) that are either dominant or recessive. The dominance or recessivity associated with a detail allele is the result of masking, by which a dominant phenotype hides a recessive phenotype. By this logic, in heterozygous offspring just the dominant phenotype will be apparent.

The human relationship of alleles to phenotype: an case

Relationships between ascendant and recessive phenotypes can be observed with breeding experiments. Gregor Mendel bred generations of pea plants, and equally a upshot of his experiments, he was able to propose the idea of allelic cistron forms. Mod scientists use organisms that have faster breeding times than the pea establish, such every bit the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster). Thus, Mendel's primary discoveries will be described in terms of this modernistic experimental option for the remainder of this discussion.

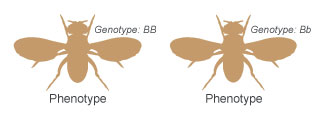

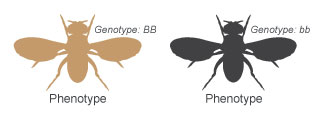

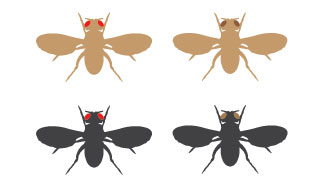

Effigy 2: In fruit flies, two possible trunk colour phenotypes are chocolate-brown and black.

The substance that Mendel referred to as "elementen" is now known as the cistron, and different alleles of a given gene are known to give rise to unlike traits. For instance, convenance experiments with fruit flies take revealed that a single gene controls wing body color, and that a fruit fly can have either a brown body or a blackness body. This coloration is a direct result of the body color alleles that a fly inherits from its parents (Effigy 2).

In fruit flies, the gene for trunk color has two different alleles: the black allele and the chocolate-brown allele. Moreover, chocolate-brown body color is the dominant phenotype, and black body color is the recessive phenotype.

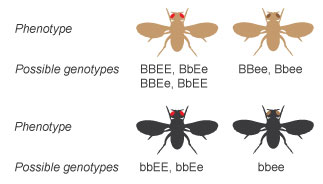

Figure 3: Unlike genotypes can produce the aforementioned phenotype.

Researchers rely on a type of shorthand to represent the different alleles of a gene. In the case of the fruit fly, the allele that codes for brown body colour is represented by a B (because brown is the ascendant phenotype), and the allele that codes for black torso color is represented by a b (because black is the recessive phenotype). Every bit previously mentioned, each wing inherits one allele for the trunk color gene from each of its parents. Therefore, each fly will carry two alleles for the body colour factor. Inside an individual organism, the specific combination of alleles for a cistron is known every bit the genotype of the organism, and (as mentioned above) the physical trait associated with that genotype is called the phenotype of the organism. So, if a fly has the BB or Bb genotype, it will accept a brown body colour phenotype (Figure three). In contrast, if a fly has the bb genotype, information technology will accept a black body phenotype.

Authorization, breeding experiments, and Punnett squares

Effigy 4: A brown fly and a blackness fly are mated.

The best mode to sympathize the potency and recessivity of phenotypes is through breeding experiments. Consider, for example, a breeding experiment in which a fruit fly with brown body color (BB) is mated to a fruit wing with black body color (bb). (The genotypes of these 2 flies are shown in Figure 4.) The convenance, or cross, performed in this experiment can exist denoted as BB × bb.

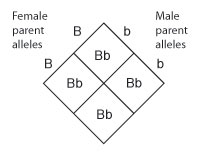

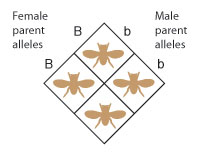

Effigy 5: A Punnett square.

When conducting a cantankerous, one fashion of showing the potential combinations of parental alleles in the offspring is to align the alleles in a grid called a Punnett foursquare, which functions in a manner similar to a multiplication table (Figure 5).

Effigy 6: Each parent contributes 1 allele to each of its offspring. Thus, in this cantankerous, all offspring will have the Bb genotype.

If the alleles on the outside of the Punnett square are paired upwards in each intersecting foursquare in the grid, information technology becomes clear that, in this particular cross, the female parent can contribute only the B allele, and the male parent can contribute only the b allele. As a issue, all of the offspring from this cross will take the Bb genotype (Figure 6).

Effigy 7: Genotype is translated into phenotype. In this cross, all offspring will accept the brown torso color phenotype.

If these genotypes are translated into their corresponding phenotypes, all of the offspring from this cross will have the dark-brown body color phenotype (Figure 7).

This outcome shows that the brown allele (B) and its associated phenotype are ascendant to the black allele (b) and its associated phenotype. Fifty-fifty though all of the offspring accept brownish trunk color, they are heterozygous for the black allele.

The phenomenon of dominant phenotypes arising from the allele interactions exhibited in this cross is known every bit the principle of uniformity, which states that all of the offspring from a cross where the parents differ by simply 1 trait will appear identical.

How can a breeding experiment be used to find a genotype?

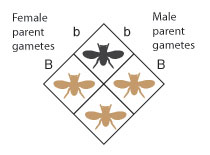

Figure 8: A Punnett square tin can assist decide the identity of an unknown allele.

Brownish flies tin exist either homozygous (BB) or heterozygous (Bb) - but is it possible to determine whether a female person fly with a brown body has the genotype BB or Bb? To answer this question, an experiment chosen a test cross tin can be performed. Exam crosses assistance researchers determine the genotype of an organism when only its phenotype (i.due east., its appearance) is known.

A test cross is a breeding experiment in which an organism with an unknown genotype associated with the dominant phenotype is mated to an organism that is homozygous for the recessive phenotype. The Punnett square in Figure 8 can be used to consider how the identity of the unknown allele is determined in a test cantankerous.

Convenance the flies shown in this Punnett foursquare will determine the distribution of phenotypes among their offspring. If the female parent has the genotype BB, all of the offspring volition have brown bodies (Figure 9, Upshot 1). If the female parent has the genotype Bb, 50% of the offspring will accept chocolate-brown bodies and 50% of the offspring will accept blackness bodies (Figure nine, Outcome 2). In this mode, the genotype of the unknown parent can exist inferred.

Again, the Punnett squares in this example function like a genetic multiplication table, and there is a specific reason why squares such as these work. During meiosis, chromosome pairs are split apart and distributed into cells called gametes. Each gamete contains a single re-create of every chromosome, and each chromosome contains one allele for every gene. Therefore, each allele for a given gene is packaged into a separate gamete. For instance, a fly with the genotype Bb will produce two types of gametes: B and b. In comparison, a wing with the genotype BB will only produce B gametes, and a wing with the genotype bb will just produce b gametes.

Figure 10: A monohybrid cross between two parents with the Bb genotype.

The following monohybrid cantankerous shows how this concept works. In this type of breeding experiment, each parent is heterozygous for body color, so the cantankerous can be represented past the expression Bb × Bb (Figure 10).

Effigy 11: The phenotypic ratio is 3:ane (brown trunk: black trunk).

The effect of this cross is a phenotypic ratio of 3:i for brown body color to black body color (Figure 11).

This ascertainment forms the 2nd principle of inheritance, the principle of segregation, which states that the 2 alleles for each gene are physically segregated when they are packaged into gametes, and each parent randomly contributes i allele for each gene to its offspring.

Tin 2 dissimilar genes exist examined at the same fourth dimension?

The principle of segregation explains how individual alleles are separated amidst chromosomes. Merely is information technology possible to consider how ii different genes, each with different allelic forms, are inherited at the same fourth dimension? For case, can the alleles for the torso color cistron (brown and black) be mixed and matched in different combinations with the alleles for the heart colour gene (red and brown)?

The simple respond to this question is yes. When chromosome pairs randomly marshal along the metaphase plate during meiosis I, each member of the chromosome pair contains ane allele for every cistron. Each gamete volition receive one copy of each chromosome and one allele for every gene. When the private chromosomes are distributed into gametes, the alleles of the unlike genes they bear are mixed and matched with respect to one another.

In this example, there are two different alleles for the heart color gene: the Eastward allele for ruby-red eye colour, and the due east allele for chocolate-brown eye color. The reddish (E) phenotype is ascendant to the brown (e) phenotype, so heterozygous flies with the genotype Ee will take red optics.

Figure 12: The iv phenotypes that tin consequence from combining alleles B, b, E, and e.

When two flies that are heterozygous for brown body color and ruddy eyes are crossed (BbEe X BbEe), their alleles can combine to produce offspring with four different phenotypes (Figure 12). Those phenotypes are brown torso with red eyes, brown body with brown eyes, black body with ruddy eyes, and black torso with brown eyes.

Figure xiii: The possible genotypes for each of the four phenotypes.

Even though merely four different phenotypes are possible from this cross, nine different genotypes are possible, as shown in Figure xiii.

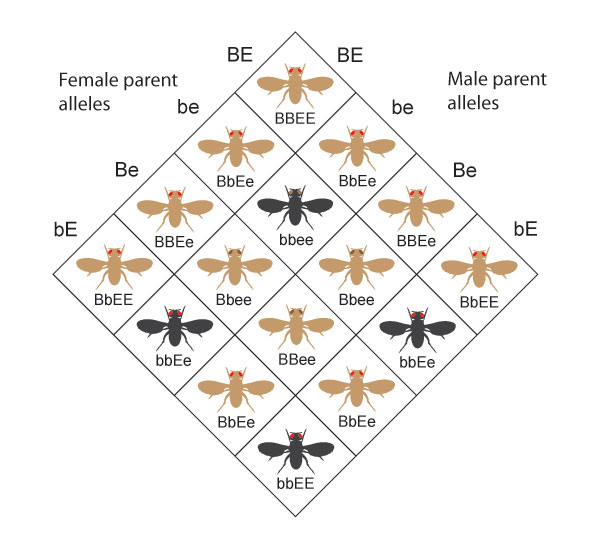

The dihybrid cross: charting two different traits in a single breeding experiment

Consider a cross between two parents that are heterozygous for both body colour and eye colour (BbEe x BbEe). This type of experiment is known as a dihybrid cantankerous. All possible genotypes and associated phenotypes in this kind of cross are shown in Figure xiv.

The four possible phenotypes from this cross occur in the proportions 9:3:3:1. Specifically, this cross yields the following:

- ix flies with brown bodies and cerise eyes

- 3 flies with brown bodies and brown eyes

- three flies with black bodies and red eyes

- ane fly with a black body and brownish optics

Figure xiv: These are all of the possible genotypes and phenotypes that can result from a dihybrid cantankerous betwixt 2 BbEe parents.

Why does this ratio of phenotypes occur? To respond this question, it is necessary to consider the proportions of the individual alleles involved in the cross. The ratio of brown-bodied flies to black-bodied flies is iii:i, and the ratio of red-eyed flies to brown-eyed flies is also 3:i. This means that the outcomes of body colour and eye color traits appear as if they were derived from two parallel monohybrid crosses. In other words, even though alleles of 2 different genes were involved in this cross, these alleles behaved as if they had segregated independently.

The event of a dihybrid cross illustrates the 3rd and final principle of inheritance, the master of independent assortment, which states that the alleles for 1 gene segregate into gametes independently of the alleles for other genes. To restate this principle using the example above, all alleles assort in the same manner whether they code for torso color alone, eye color lonely, or both torso color and middle color in the same cross.

The impact of Mendel's principles

Seminal experiments on inheritance

Mendel'due south principles can exist used to understand how genes and their alleles are passed down from ane generation to the next. When visualized with a Punnett foursquare, these principles can predict the potential combinations of offspring from two parents of known genotype, or infer an unknown parental genotype from tallying the resultant offspring.

An important question still remains: Do all organisms pass on their genes in this way? The reply to this question is no, but many organisms do showroom simple inheritance patterns similar to those of fruit flies and Mendel's peas. These principles form a model against which different inheritance patterns tin be compared, and this model provide researchers with a way to analyze deviations from Mendelian principles.

Source: http://www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/inheritance-of-traits-by-offspring-follows-predictable-6524925

Posted by: stormplacrour.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Parent Genes (Genetic Makeup) Called?"

Post a Comment